By Osezua Stephen-Imobhio

In an era where algorithms on platforms like Netflix and YouTube amplify Western narratives, African cultures risk being marginalized. The dominance of Western media—from Hollywood blockbusters to fast-food advertising—has fostered a global monoculture that threatens indigenous languages, traditions, and values. This cultural erosion is more than a loss of heritage; it represents an existential crisis. As the African proverb warns, “A man who loses his culture is like a tree without roots.” However, film festivals hold the power to resist this homogenization, serving as dynamic platforms for social change, cultural advocacy, and the reclamation of African identity.

Digital algorithms prioritize engagement over diversity, disproportionately promoting Western content and creating a feedback loop where African stories, told in indigenous languages and rooted in local philosophies, are overshadowed. For example, YouTube’s recommendation system often favors English-language action movies over Yoruba-language films, while streaming platforms prioritize Eurocentric storytelling. The result? A generation increasingly disconnected from its heritage, adopting borrowed cultures, speaking foreign languages, wearing foreign attire, and celebrating foreign holidays. “Show me a man living a borrowed culture,” the article laments, “and I’ll show you a man who has lost not only his identity but his essence.”

Despite this, African film festivals, such as the African Indigenous Language Film Festival (Ailff) and FESPACO (Pan African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou), challenge this trend by focusing on narratives that reflect Africa’s diverse cultures. These festivals act as living archives by preserving languages, showcasing cultural rituals, and reclaiming aesthetics. Films like Kunle Afolayan’s “Aníkúlápó,” shot primarily in Yoruba, have sparked renewed interest in the language among urban youth. Documentaries like “The Art of Ugandan Bark Cloth” immortalize endangered practices, while dramas such as “Lionheart” (2018) showcase Igbo traditions of leadership and community. Costume design in films like “The Woman King” (2022) celebrates pre-colonial attire, challenging the notion that modernity requires Western dress codes. By screening such works, festivals transform cinemas into sacred spaces where culture is both preserved and reimagined.

Film festivals further amplify marginalized voices often ignored by mainstream media. For instance, the Zanzibar International Film Festival platforms Swahili poets and filmmakers addressing gender inequality through matrilineal histories, while South Africa’s Encounters Documentary Festival highlights post-apartheid land rights struggles, giving agency to communities silenced for decades. These stories do more than inform—they provoke dialogue. After the 2019 screening of “Sew the Winter to My Skin,” a South African epic on anti-colonial resistance, audiences mobilized to protect historical sites threatened by urbanization.

The adoption of Western names, diets, and value systems reflects a deeper psychological colonization. A child named “Brian” in Lagos may never learn his grandfather’s Yoruba name, “Babajide” (“father awakes”). A family eating processed pizza in Nairobi may forget the medicinal wisdom of fermented ugali. Film festivals confront this crisis by curating themes that interrogate identity and hosting post-screening debates with elders, historians, and linguists to bridge generational divides. As Malawian filmmaker Joyce Mhango Chavula argues, “When we see our dances, our rituals, and our heroes on screen, we remember who we are.”

To maximize impact, African film festivals must adopt intentional programming. This includes decolonizing screens by prioritizing films that subvert Western tropes, engaging youth by partnering with schools to screen age-appropriate films in indigenous languages, and utilizing digital innovation by using AI ethically to promote African content on festival streaming platforms. The African Film for Development Festival (AFIDFF) exemplifies this approach, using virtual reality to immerse audiences in recreated ancient Benin City.

Film festivals are not mere entertainment—they are acts of resistance. By centering African voices, languages, and values, they revive extinct traditions and chart a path toward cultural sovereignty. As audiences, filmmakers, and advocates, we must demand that festivals prioritize thematic thrusts rooted in authenticity. Let us weaponize storytelling to reclaim our essence, for as the Ghanaian proverb reminds us: “The ruin of a nation begins in the homes of its people.”

Viva Africa! Our screens will be our shields; our stories, our salvation.

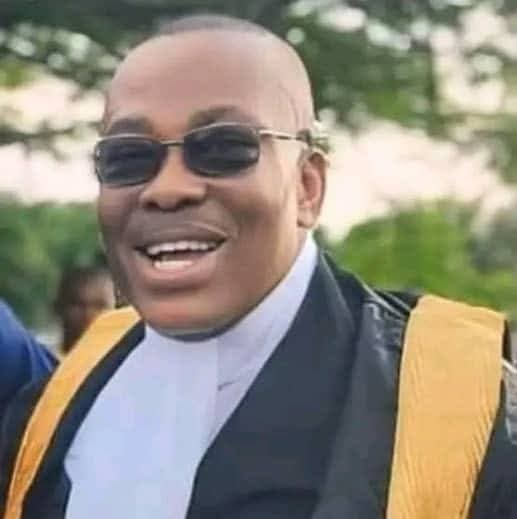

*Osezua Stephen-Imobhio (Founder, African Indigenous Language Film Festival)